Interview with Fanny Oppler

- Designer, Interview

Table of Contents

Hi Fanny! Can you present yourself in a few words?

Hi, I’m Fanny Oppler, I’m from Basel, Switzerland. I have a bachelor’s degree in visual communication. I had my first internship with “Hauser, Schwarz” and five years later, I’m still working there. I’m the only employee. We work with cultural actors. We do visual communication such as posters, websites, animation, signage and exhibition design. The rest of my time, I am a board member of the community centre One Happy Family (OHF) and a representative of The Lava Project, both based on the Greek island of Lesvos.

How did you come with the idea to go to Lesvos?

I was planning, with my brother, to get a van and travel while doing design work for locals we would meet. At that time, I was doing the transcription of interviews for a documentary called “Volunteer”. It was about an NGO doing humanitarian work in Thessaloniki, Greece. It hooked me to go there. Instead of just travelling, we both applied to this NGO. They told us to go to the island of Lesvos instead where they had a community centre near the two camps of Moria and Kara Tepe.

To our surprise, there was nothing. The project was just starting. Luckily, we came with our van full of tools, so we started helping and building… it’s only after some days that we all came up with the name: One Happy Family.

After a few weeks, we left back home and then heard that the organization suddenly dropped the project. The volunteers on the ground contacted us to rescue the centre, create an organization and start to search for funding. So, we just did it. Since then, my brother and I are part of the board. It’s crazy because, within this small team, all had such different skills, so we were really efficient. We started presentations in Switzerland, created fundraising, wrote to foundations… things I had never done before. It kind of worked out. We had the money for one week. Then, many volunteers joined. It helped us to spread the message, connect with their communities and make this project survive.

Can you tell us more about OHF?

The main goal of OHF is to work together: locals, volunteers, helpers (note: volunteers from the camp) and visitors. Our baseline is to work “with the people not for the people”. It was a natural behaviour to have for such a project. Doing so, we get inputs from all kind of people so it’s a really creative place with many activities. A challenge is never left alone because we always have a skilful person to tackle the problem. Now the coordination team on the ground has a fair diversity that is reflected on every decision.

How would you describe OHF? A humanitarian or a social NGO?

When OHF opened as a community centre, I thought it was more of a social work because everything is about the community and working together. But of course, we also gave out food, had a hygiene shop, provided basic needs to people, especially during the winters. So, it’s a bit of both. The atmosphere, the spirit is more social, but we can adapt to the context.

It reminds me of my work with Campfire Innovation. We observed good grassroots NGO and tried to define their common characteristics. We defined "smart-aid" to be a good balance of efficiency, dignity, collaboration, technology and scalability.

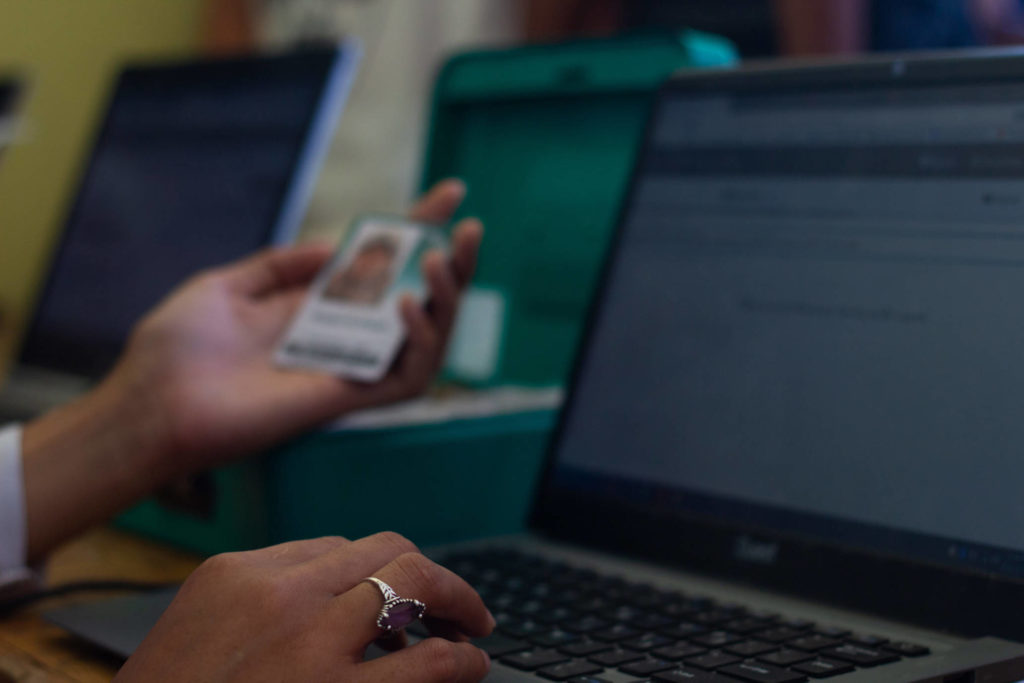

About the technology, we have a free-currency called Swiss Drachma that visitors can receive at our “bank” in the centre. We are Swiss so of course, we needed a bank… it’s always the joke but the technology part is actually important. They register, get two Drachmas per day, and can use it for different activities within the centre. It brings back some normality and dignity where people can choose what they want to do. It’s like a basic income. I have observed other projects with no technology, and you realise that a simple ticket system can provide a more equal service.

Something I'm often saying when I'm talking about my experience on Lesvos is that "in three years, I have met only three designers". I have the chance to be talking to one of them right now, what is your perspective on it? In your network, do you have designers that followed a similar path?

Designers I know engage more in organisations that are in town, here in Basel. I have one friend who is very active in supporting refugees here. He is the founder of an NGO, so he does speeches around and he is a self-employed designer doing websites and communication. So, clients hear from his work in the aid sector and are more willing to contact him. Every time there is a new festival, I see his graphic design there.

But I haven’t met any designer on Lesvos, except you. I have heard of Office of Displaced Designers and some work they did with information design.

Information design such as leaflets, signage, icons, translating, making information visible is the main field designers are interacting with on the island. Information is a real challenge. How to share a message to everybody knowing we all have different cultures and languages? It’s something you don’t learn at school. I could never do design in Lesvos the way I do it in Switzerland. Both must be practical and as simple as possible.

- In Switzerland, I would make it provocative because you must make an effort to be visible. I could care about the tiny details.

- On Lesvos, you must break down information into the very basic and show it in a nice way.

NGOs wouldn’t be able to think in advance what they would need from a designer. The context changes so fast that they would know only when the problem arises. And on the following meeting, your solution must be ready and working. It must be fast, readable and cheap. That’s maybe why it’s not so appealing for designers?

I also think the state of mind of a designer can be really useful here because we know how to work with projects. We can guide the process and welcome change along with the project. Even if it’s a two-day project, we know how to start and get it done. It’s a skill that is really needed on Lesvos. When we worked on the library van: we looked at it, made a plan, measured stuff, got the material… and while working, the project evolved and changed. Some people were confused that the plan changed so many times but for us, we knew it was part of the process. I’m sure different designers have different methods but maybe this project mindset is a common skill.

You said the board team was very diverse, what did you bring as a designer?

Of course, I created the website with my brother. There were several things I could start quickly such as all the communication for the fundraising: flyers, posters, dossiers, …

The logo was created by a helper. It is a representation of OHF diversity. I worked on it to make it more professional. Communication can’t be too chaotic; it must follow certain standards, especially for fundraising.

Otherwise, I didn’t bring something like a “design package”. It was always a collaboration with a team of people. I like to start new things and do stuff. See if it works well and if not, change it or do something else. I really like this flexibility. I brought ideas.

It sounds like an iterative process or an agile method. Is that something you see a lot on the humanitarian sector?

If you plan something well for a long period of time and then you do it properly. Maybe it works but maybe not… and then you waisted a lot of time doing the planning.

This island is crazy, things change every day. It doesn’t make sense to have a long planning process because half a year later, everything is already different. So, in this chaos, it’s better to do something and adapt based on the skills and context. It’s easier to get something done. And it’s not that much of a fuck up if it doesn’t work out, because you haven’t lost half a year to plan it. I mean with this new context I don’t know.

Note: The interview was conducted on 15th of September 2020. A few days earlier, a fire completely burnt down Moria camp, letting 13.000 people on the street.

Can you tell me more about your life balance back in Switzerland?

The company I’m working for is really supportive. So, I work 3 days a week for them. Thursday and Friday are OHF time. I wanted to keep my Sundays off, but it didn’t work out so well. We often have meetings with board members on Sunday and extra work in the evenings. I like to do stuff so it’s okay. I’m getting nervous if I have nothing to do.

Now is also the time to prepare for Christmas fundraising. That’s when we get most of our support. People give a lot of money before Christmas, but we always have to give something back, as a present, so there is always a ton of things to do. It’s a project I took over. I designed Safe-Passage socks. Now we are importing olive oil from Lesvos. We have a market stand and an online shop. So, from October to December, my main task is to send socks to the whole world, my room is full of boxes. It’s also a way to talk about OHF and what we are doing on the island but clearly, there is not such a thing as a work-life balance during this period.

Is the work you're doing enough to sustain life?

Of course, I live in a shared flat, I couldn’t live by myself but that’s fine with me. I don’t get money from OHF because I won’t feel okay to oversee fundraising and use it to pay myself. Other people on the ground need it. So, I get exactly the amount of money I need from my work. I don’t have to cut out stuff. I can afford to travel for example, I mean I won’t anyway. I’m going to Lesvos tomorrow for six months.

What are your plans once reaching Lesvos?

I have no idea what I’m going to do since the fire broke out… but nobody has. I have to quarantine for at least 7 days and from there everything can change so we will see. As a legal representative of OHF, I will have a lot of administrative work to deal with. The Greek bureaucracy is the worst.

The context will change in the next weeks and we must adapt to the situation. But we will talk about it on time. Our centre is a large place and can provide a lot as an emergency response. The plan was to open again and become a more skill-development centre. But of course, first, there are basic needs to be covered and we are collaborating with other NGOs.

Have you considered to do humanitarian work on a full-time base?

Yes, I half-way applied for a Master in humanitarian response but in the end, I am not motivated to go back to school for two years doing theoretical work. I am now going to Lesvos for six months; I prefer to learn by doing. I don’t have a special attachment to the island, but I wouldn’t do humanitarian work in Yemen for example. It’s mostly about OHF. That’s also why I didn’t apply for the Master. It’s because I should have given up on OHF to be able to finance myself; with a freelance job or working in a bar. Things, I didn’t want to do again.

Do you think that Switzerland, by its history in the humanitarian field, is more active?

(Laugh) There is this well-known “humanitarian tradition” here. I just watched a video from a comedian/rapper. He explains that we are not representative of this tradition anymore if “we don’t act now”, it’s a funny video. We are often pictured as good people: we didn’t do the war; we have the Red Cross but I don’t think it’s a tradition anymore. The fact that we have a good life here is probably a better explanation: we have time and money to do things.

After the fire in Moria camp that put 13.000 people on the street, Switzerland is now taking 20 people. So embarrassing.

Would you have someone in mind for us to interview?

Lukas, my brother. He did a Bachelor thesis about community building. Beside OHF, he went to India for a similar project and Mozambique. He has more of a design mindset and started various organizations. His school was very engaged in social projects, so he probably has an interesting network of people regarding the topic of today.

Or Marcel Gross, the person I talked about who is working with associations here in Basel.

Thank you for your time, Fanny!

Cédric Fettouche

Cédric Fettouche works as a design strategist for the European Commission on the New European Bauhaus Initiative.

After three years of humanitarian experience in Greece and Central Mediterranean, he founded the NGO Humanitarian Designers (HD) in 2021 to bridge the gap between the design and humanitarian sectors.

Passionate about design and societal challenges, he strives to experiment his committed vision into new sectors, and share his learnings back to the design communities. You can contact him on Linkedin or on the HD Slack.