Interview with Caroline Grellier

- Designer, Interview

Hi Caroline, can you tell us about your journey from France to Benin?

This is a long journey. I always enjoy hearing new stories from people so I hope that my journey can inspire young designers to take action.

Everything started in 2013 when I studied product design in École Boulle, France. During these studies, the school organised a trip to Benin in partnership with La Cité de l’Architecture. It was the first time that I was visiting West Africa. It opened my mind. I had a real cultural shock… in a very positive way.

So, one year later, when I graduated from my Master’s degree, I applied and received a grant from the Municipality of Paris to travel back to Africa for a one-year break with a Fab Lab in Lomé, Togo. During this year, I met all the communities of makers from West Africa: Abidjan, Ouagadougou, Takoradi, Dakar, … It comforted me to say that West Africa was full of brilliant designers. Surprisingly, none of them, even the most experienced, called themselves designers because they didn’t have degrees from formal design schools. Instead, they were all seeking advice from me, the official designer.

These observations accelerated my will to conduct more research about endogenous knowledge and the place of design in a multicultural context. I started to analyse the differences and similarities between expert and non-expert pedagogies, and the place of a foreigner intervening in such a context.

Editor’s note: in biology, endogenous means that it originates from within a system. Understand “endogenous knowledge” as the knowledge that originates from within a system such as a culture or a community.

Inspired, I went back to France in 2017 to continue this research during a Master’s degree in Design Innovation Society, at the University of Nîmes. I collected more tools and methods to facilitate collaborative and innovative projects. Then, I immediately went back to Benin for the post-graduate internship with the University of Abomey-Calavi (Cotonou) on another great topic of interest: the creation of local biobased materials which I experimented with for a few years by founding Termatière.

Since 2018, I have been working with Africa Design School during the week and with the association L’Atelier des Griots during the weekend:

– The French design school “L’École de design Nantes-Atlantiques” contacted me because they had just won a call for tender, organised by the Beninese government, to create the first design school in West Africa. They wanted me to become the first Program and Executive Director of Africa Design School. I accepted this great opportunity as I always wanted to create a school. But after two years of hard work, I quitted this position and I am now solely teaching to Africa Design School’s students.

– L’Atelier des Griots is a Beninese association specialised in architecture and design. They are supporting and revitalising districts by collaborating and co-creating with local communities.

The contrast between my full-time work in a large building with computers, classrooms, and teachers, versus my weekends with a non-formal community-led association, is sometimes funny. The dynamic is very different but they are both teaching relevant skills, which is very inspiring.

What is L’Atelier des Griots? How does it work and what are you doing there?

It was created in 2013 by Habib Mémé, a Beninese architect, who co-founded it with his former teacher from the Boston Institute of Technology: John Stephen Ellis. Their goal is to rethink the role of an architect in Africa and to desecrate the vision people have about architects; to give it a more human-centred/community-led approach. Because architects are not only graduating to draw nice penthouses, they also intervene in less wealthy districts.

For example, we had a project on a youth house in the district of Akpakpa Dodomey Enagnon. This district was a bit abandoned by the state and didn’t have a good reputation. We went there, spoke with the local student association, la Maison des Jeunes de Enagnon Cotonou (Maps), and involved the surrounding communities. We worked together to revitalise the courtyard, which was the only socialising space they had for public events: meetings, weddings, baptisms, and diners during special national holidays were all happening there.

What is unique about our work is that we are becoming part of this community: we observe, discuss, and accompany them in their reflection and research. But, it’s the youths who initiated and led the project; we were just a triggering element. They took measurements, did the mapping, proposed and implemented new solutions and usages… they did the work.

Do you think that one of the most important attributes of designers is to collaborate and co-create?

Exactly, I believe that community-led design has a lot to bring. My job as a designer is mainly about mediating and facilitating creative workshops so locals can create solutions that best fit their needs.

I have lived seven years in Africa, so I do have a certain understanding of the context now, but I am still an Occidental/European: my perception and way of thinking are inevitably different. It’s important to realise that the expertise I am bringing from France isn’t the one truth: a lot of endogenous knowledge, that I am not aware of, is shared among local communities. The Beninese philosopher Paulin J. Hountondji and the Burkinabe historian Joseph Ki-Zerbo are great resources to learn more about endogenous knowledge.

Our conversation is slowly going to the decolonising design movement. Let’s dive in. What is your experience?

It’s true. As soon as I arrived in Benin in 2013, I immediately realised that Beninese people had a different idea of what is design. My practice of design was different; there wasn’t a one size fits all about design practice. But I had never put these two words together until a few years ago.

I advise people to read the work of Dr Amollo Ambole who wrote Rethinking design making and design thinking in Africa issued in 2020:

– When it comes to decolonising the design history, she explains how Western cultures simply erased the pre-colonial history of design by teaching to the world how “design appeared during the Industrial Revolution”.

– When it comes to decolonising the design practice it might be a bit harder to assimilate. A simple example is the world-known Double-Diamond method used by many designers. This method was created by the British Design Council for British designers and companies. Should we use it the same way in a foreign country where the language is different and, therefore, the way to build our thoughts is different? As an Occidental, how can I know if the tools I learnt in school are adapted to non-Occidentals countries? Should we just propagate our Occidental approach to countries even though we know that they have a different culture and practice of design?

It became a true revelation that is now guiding my work and answering a lot of my previous assumptions.

If the decolonising design is partly about empowering endogenous knowledge, have you spotted major differences in design practices?

In Fab Labs, people tend to be very practical. I remember that I was there with my pencils trying to draw ideas, and people around me had already found solutions with cardboards and quick prototyping tools. It’s funny to see how this Maker movement has spread back to Occidental countries with the Jugaad trend (“being resourceful in challenging conditions”).

The Maker movement is also a worldwide online movement made of open source projects and where everybody can iterate on others’ solutions. This online multiculturalism is a great source of design decolonisation because it erases borders between the Global South & Global North by showing that every community has a unique set of endogenous knowledge that is often better to answer local challenges. It empowers people and communities to adapt ideas to their context by using their skills and resources. To achieve this result, it’s of course important to not have one culture oppressing another.

Maybe you want to talk a bit more about the Maker community? in France, we do have fab labs, jugaad, Low-Tech, … but it seems that it’s more developed in West Africa, isn't it?

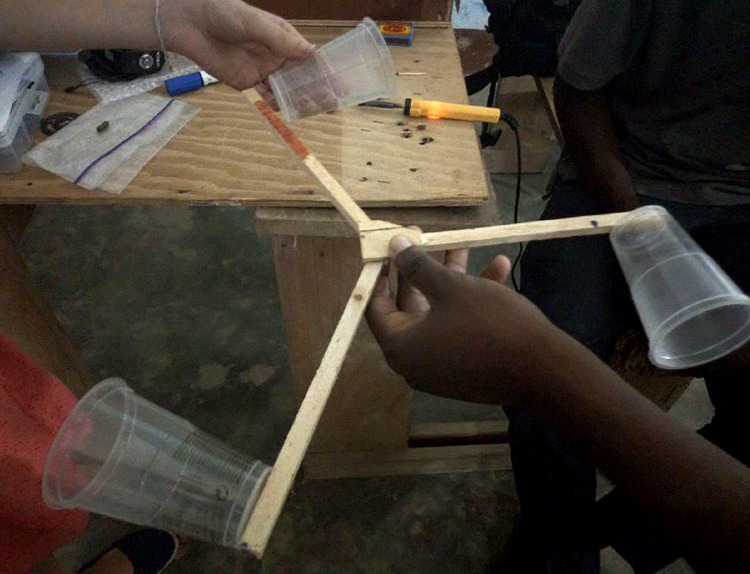

Well, they have a long history indeed, I wrote for three years about them on Makery.info. By experience, African fab labs are much more often established as community-led spaces than in France. For example, the Wakatlab in Burkina Faso, was the first fab lab in West-Africa, back in 2011. For many years, it was just a friends’ gathering in someone’s house with the common goal to learn together and prototype ideas to improve the district’s life. Their first project was a wind turbine made of recycled materials.

On the contrary, in Europe when the trend was at its peak, there was a lot of funding to create fab labs with fancy prototyping machines but very few thoughts on how to create the communities in charge of maintaining and developing these places. There were a lot of fancy fab labs but no interesting projects. People were mainly going there to get something and not to share something.

So, in West Africa, we don’t have 3D printing and laser cutting machines, but we have the same core team of people since the beginning. And, there isn’t one teacher: experts and non-experts are equally learning which nurtures creative projects. Co-learning is key in the Maker movement.

Your thoughts and research seem to lead your work. Do you see your research as a way to improve your profession in a committed way?

Yes, research has always been complementary to my work, especially since I heard about the decolonising design movement. But research is feeding my practice of design rather than the opposite.

Research can support design schools. I am sure that, in the future, more design schools will emerge in Africa. If these schools are initiated by Occidentals, it’s very important to arrive with the right mindset and ask ourselves: “what are we going to do here? How? Why? For whom?”.

Decolonising design has been researched by dozens of researchers for the last 15 years already. But mainly by researchers from the Global South, in English-speaking African countries. On the contrary, I was surprised to see that decolonising design was almost nonexistent in French-speaking countries. I think it’s an important conversation to have because I can observe daily the aftermath of colonialism in West Africa (Editor’s note: Benin is a former French colony) and how a lot of local history has been erased by the Occidental’s version of history.

My assumption is that to implement a decolonised design, one must understand the endogenous culture, especially in this modern globalised world.

So decolonising design is about history, culture, practices, … do you have any other example? Because I think that a lot of people are not aware of it yet.

For example, last week, I had a student who presented a project about a dress for women. He started to present his research about the four seasons and how his dress could adapt to all of them, including winter. In Benin, we have only two seasons, dry-season and rain-season. And I don’t think we ever had snow. So, I was a bit surprised when he said this dress was for Beninese people. There is a part that is weld into colonialism and that cannot be fixed in a matter of years.

We are living in a very interesting period where a lot of simultaneous, yet distinct societal challenges are being raised and fought. What would you say to designers who were never challenged by such topics?

It’s important to keep this designer mindset of being curious about the world we are living in, about ourselves, and our practices. I don’t have bad feelings about designers who don’t care about decolonising design because it might just not relate to their lives. On the contrary, all the designers who are going to Africa to initiate design projects should be aware of decolonising design because I do think that importing Occidental design methods to African countries is a form of colonialism. That is problematic.

I am getting a lot of inspiration from US teachers who are teaching Black design history. In my class, we have Beninese, Senegalese, Cameroonians, Ivorians, … there is no way I will only talk about Occidental designers. A lot of our challenges are about representativeness: students will “take example on” and assimilate their style and work to those celebrities so we must show major African celebrities who innovated and created outstanding work in their professional fields.

Without such research, we will continue to import our knowledge and participate in a modern form of colonialism. It’s not because there aren’t any official design schools in a country that we should have the right to dictate our version of what is design.

With the idea to guide young designers, what would be your advice in starting such a journey?

I think it’s important for every human being to get out of their comfort zone, to go and discover the world surrounding them, especially as a French student. We have a lot of opportunities out there: scholarships, grants, Erasmus, internships, … Ten years ago, I wouldn’t have expected to now be living in Benin. But the opportunity I was given by the school, then by the grant, to travel there just triggered me in a very powerful and positive way. Being proactive may change your life and help you to develop a real-quick design maturity.

Then, I would say that it’s important to continue learning. It’s not because you graduated that you know it all, especially as a designer. We should remain curious about our profession because what we learnt 10 years ago might have completely changed and evolved. And if you need so, you can always go back to school later.

Finally, I think that, more and more, design is becoming political. It was already before of course, especially in the ’70s, but there is a new uprise in becoming a designer with militant ideas. My cause is multiculturalism: I think it’s important to preserve all our differences and to avoid creating a single globalised identity. But we all have different topics of interests. So, I am inviting all the young designers to take a stand and defend their opinions publicly.

Thank you Caroline!

Thank you too, it is a great pleasure to have an open stage to share these topics because there are not a lot of resources available.

Where can you connect with Caroline?

Editor’s note: article translated from French by the author of the interview.

Cédric Fettouche

Cédric Fettouche works as a design strategist for the European Commission on the New European Bauhaus Initiative.

After three years of humanitarian experience in Greece and Central Mediterranean, he founded the NGO Humanitarian Designers (HD) in 2021 to bridge the gap between the design and humanitarian sectors.

Passionate about design and societal challenges, he strives to experiment his committed vision into new sectors, and share his learnings back to the design communities. You can contact him on Linkedin or on the HD Slack.

This article is very knowledgeable